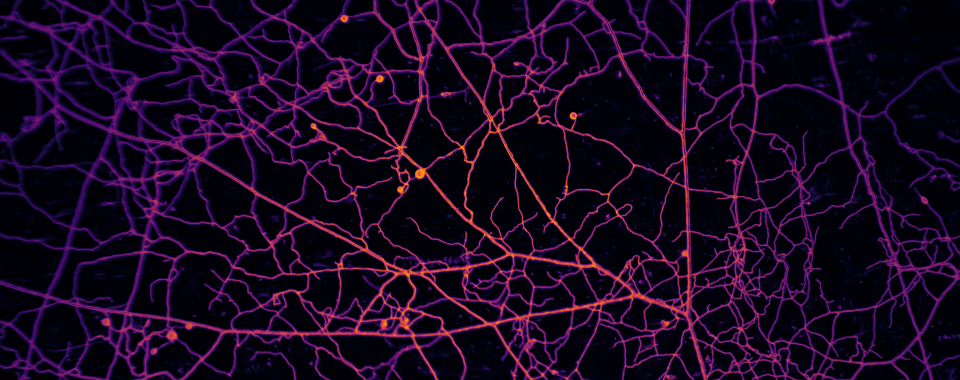

Image by Loreto Oyarte Gálvez, VU Amsterdam, AMOLFImage by Loreto Oyarte Gálvez, VU Amsterdam, AMOLF

By Scott Lyon

Feb. 26, 2025

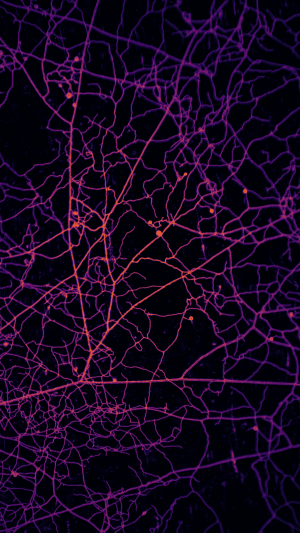

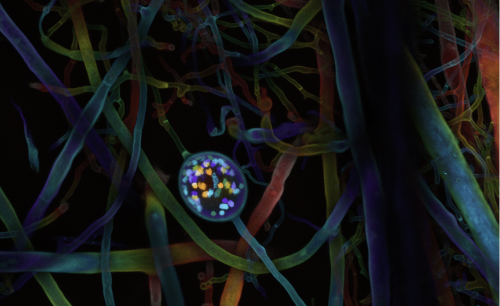

For as long as plants have lived on land, fungi have sustained them. Beneath every giant sequoia, every wheat stalk, every black-eyed Susan, hidden webs of filigreed mycelia permeate the plants’ roots and tie them into the surrounding soil. The fungi’s hollow tendrils forage for nutrients, and they transport those nutrients to the plants’ roots in exchange for carbon, in the form of sugars and fats.

Our entire planetary ecosystem would cease to exist as we know it without this complex relationship. And yet the slow pace of growth and the subterranean environs make these organisms and their partnerships stubbornly hard to study.

Now an international team from multiple institutions including Princeton University has devised a way to watch these mycorrhizal fungi in stunning detail, revealing key mechanisms that have enabled them to solve extraordinary problems for roughly half a billion years.

“Under the ground, there are all these things happening that no one ever thinks much about because they don't see them,” said Howard Stone, Princeton’s Neil A. Omenn ’68 University Professor of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering and one of the study’s authors.

Over the course of several years, a team of 28 researchers from the Netherlands, France and the United States pieced together a picture of, "not only how the architecture of these networks gets created, but also the fluid motions that are happening inside these long tubes, that are about one tenth the diameter of the human hair,” Stone said.

The closer one looks at these hairlike tubes, the more puzzling they become. The fluids carrying sugars and fats and those carrying phosphorous and nitrogen flow in two different directions within the same space, for one thing. And while these flows are largely consistent over the long run, in places they speed up and slow down, change directions, and solve all kinds of dynamic problems in ways that confound and inspire in equal measure.

The paper’s senior authors include evolutionary biologist Toby Kiers of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and the Society for the Protection of Underground Networks (SPUN); biophysicist Thomas Shimizu, a group leader at the AMOLF Institute in Amsterdam; and biologist Merlin Sheldrake of VU Amsterdam and SPUN.

The study, published Feb. 26 in the journal Nature, spelled out three main findings.

“First, the fungi favor opportunities in the future over gains in the short term,” Shimizu said in a video released by the researchers.

He said the fungi develop specialized growing tips that act as pathfinders, exploring new territory and pulling with them a massive network of “intricate, lacelike mycelium that is just dense enough to forage for phosphorous.

"That’s the commodity they can exchange for more carbon,” he added.

The networks are both expansive and efficient. They are responsible for storing around 13 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year, more than a third of global annual fossil fuel emissions, according to the researchers. The fungi use that carbon to grow and to weave structure into the soils, preventing erosion.

Kiers, the chief scientist and executive director at SPUN, said the study's second finding is the most interesting: that the nutrient-rich fluids inside the hyphae move in two directions at the same time.

“We know that two-way traffic is more efficient than one-way traffic, but it can also be prone to congestion,” she said.

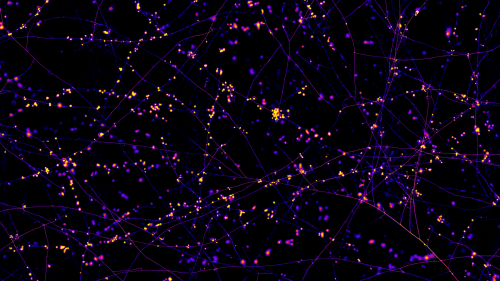

By following around 100,000 trajectories, the team discovered that the fungi adapt to congestion by widening and increasing their flows in areas with greater demand for resources, such as near plant roots.

As Kiers put it in a popular TED Talk, they trade where demand is high.

The third finding is that the fungi don’t rely on centralized decision making but instead leverage local conditions to define behaviors. “For example, when a growing tip encounters another branch of the network, they bump into each other and they just fuse,” Shimizu said. It’s an “elegant strategy for avoiding overbuilding,” he said, while balancing the need to extract nutrients and explore new areas.

The team used a specially designed robotic microscopy system that automated data collection and worked round the clock for nearly three years, allowing them to analyze more than 30 times the amount of data they would have been able to collect manually, according to Shimizu.

And it was that volume of data that enabled this view into how these fungi live and work: how they have sensed their environments, regulated themselves, solved complex transportation and trade problems and sustained plant life for hundreds of millions of years.

The paper, “A travelling-wave strategy for plant-fungal trade,” was published on Feb. 26 in the journal Nature with the DOI 10.1038/s41586-025-08614-x. The study was funded in part through the High Meadows Environmental Institute’s Biodiversity Grand Challenges Fund, the Human Frontier Science Program, Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, the Grantham Foundation, the Paul Allen Foundation and the Schmidt Family Foundation.

Shimizu, Kiers, Stone and Sheldrake are available for interviews. Please contact press@spun.earth.